In 1956, M. King Hubbert predicted that crude oil production in the U.S. (ex-Alaska) would peak in rate around 1970, to be followed by a long, irreversible decline. Hubbert nailed the timing of the peak, and in doing so, cemented his status as a technological visionary among neo-Malthusians and opponents of fossil fuels.

The method Hubbert employed to make his prediction is simple and elegant, almost trivial in its application. But is it valid? Should we base policy decisions on its conclusions?

Before answering that question, consider that Hubbert’s 1956 paper[1] contained a similar prediction: that Lower 48 natural gas production would peak in the early 1970s. In a classic case of confirmation bias, Hubbert’s 1978 update[2] declared his gas prediction correct (as with oil, he had missed the rate prediction on the low side). For Hubbert, gas had begun its “inexorable decline” right on schedule.

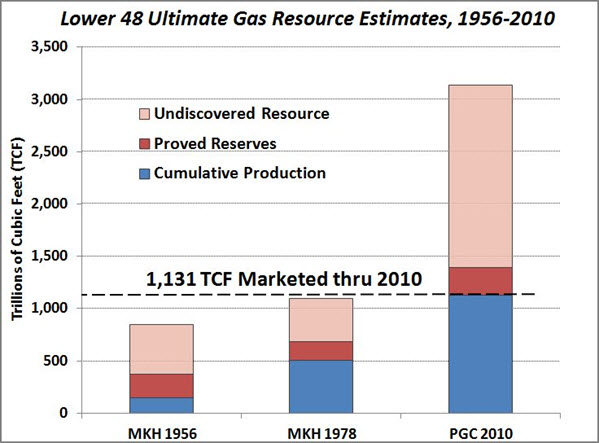

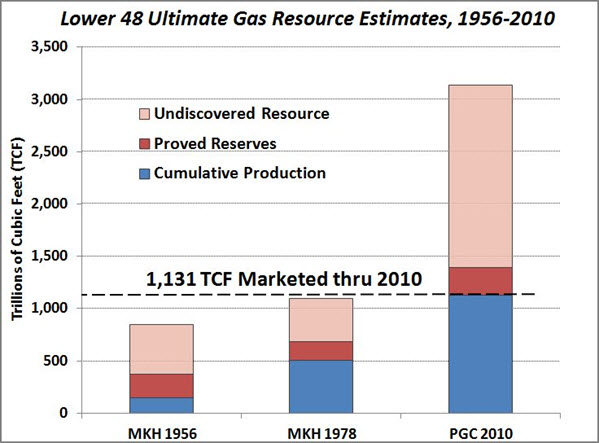

In 1956, Hubbert’s estimate of the amount of natural gas that would ultimately be consumed in the U.S. was 850 trillion cubic feet (TCF).

In the 1978 update, Hubbert increased his estimate to 1,103 TCF, but considered that value to be on the high side.

By the end of 2010, we had produced and marketed 1,131 TCF from the Lower 48, more gas than Hubbert thought would ever be possible (Figure 1). We are in the midst of a natural gas boom, with gas production now exceeding the peaks of 1973: rates are over three times higher than the 7 TCF per year Hubbert foresaw for 2010 (Figure 2). The Lower 48 resource base is some 3,100 TCF, three to four times Hubbert’s earlier estimates.[3]

Peak Oilers rarely mention Peak Gas. Hubbert expected his method to work for all resources; why did it fail with respect to gas? The answers to that question shed light on the shortcomings of Peak Oil Theory, and reveal the reasons why it should not be used as a policy-making tool.

Fig. 1: Lower 48 Ultimate Gas Resource Estimates, 1956-2010. MKH = M. King Hubbert. PGC = Potential Gas Committee.

Fig. 2: Hubbert's 1956 & 1978 Estimates vs. Actual Production

Shortcoming #1: Hubbert’s technique depends entirely upon the estimate of the ultimate resource base. Any extrapolation of historical trends contains only the information embedded in the history. There is no way to anticipate “game-changing” developments outside the confines of the history upon which it is based. A forecast of a limited future thus becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy if it is used to set policy.

Shortcoming #2: “Hubbert’s Peak” is the ultimate ceteris paribus analysis. Problem is, all other things are never equal, particularly in the realm of economics. Hubbert’s equations worked well in his experience, so well that he accepted them as immutable laws. Hubbert showed little concern for how changing policies or economics might affect his resource estimates (see Shortcoming #1).

Shortcoming #3: We are all limited by our imaginations. Hubbert could not imagine economic production of hydrocarbons from water depths over 600 feet; we now have production in nearly 10,000 feet of water. Shale rocks were never considered to have economic potential. Moore’s Law has enabled accomplishments in drilling and exploration beyond Hubbert’s wildest dreams.

Continue reading →